Sherlock Holmes: A Travel Through Time

by Bethany Wagner

For over a century, 221B Baker Street referred to a small flat in Victorian London, land of gas street lamps, long skirts, and a thick layer of murder and scandal behind the thin veil of classical Victorian “properness.”

For over a century, 221B Baker Street referred to a small flat in Victorian London, land of gas street lamps, long skirts, and a thick layer of murder and scandal behind the thin veil of classical Victorian “properness.”

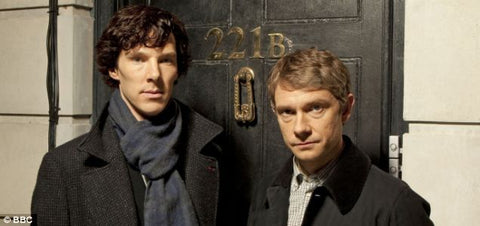

Today, 221B Baker Street still transports readers of Sir Arthur Conan Doyle’s beloved Sherlock Holmes mystery stories to that Victorian London scene. But the famed address now also brings viewers of BBC’s television series Sherlock to modern-day London, where an elusive, brilliant, cold detective named Sherlock Holmes still fights crime with his good friend Dr. John Watson.

As a modern-day adaptation, Sherlock must of course make changes to the original stories to make them fit today’s time period. Technology is perhaps the biggest change influencing the stories. Taxi cabs replace horse-drawn carriages. Villains and victims, policemen and detectives, often communicate over texts. Police, forensic scientists, and criminals use state-of-the-art technologies. Doyle’s original stories are written as memoirs narrated by Watson, who is recording his harrowing adventures with Sherlock. In the TV series, Watson records each case on an online blog.

BBC’s reliance on Doyle’s stories varies. In some episodes, the parallel lines are easy to draw. “A Study in Scarlet” became “A Study in Pink.” “A Scandal in Bohemia” became “A Scandal in Belgravia.” “The Hounds of the Baskervilles” became “The Hounds of Baskerville.” “The Final Problem” became “The Reichenbach Fall.” These episodes are very loyal to the original stories, featuring nearly identical mysteries and main plot points, though in a completely different setting.

Other episodes take more liberties, including entirely new mysteries for Sherlock to solve. But these still rely on Doyle’s classic material. For example, in “The Blind Banker,” coded messages and artwork throughout the episode alludes to three original Sherlock Holmes stories.

And even with these intentional changes to the stories, adapting them to a completely different time period, Sherlock certainly stays true to the original characters Sherlock Holmes and Dr. Watson. Self-described as a “high-functioning sociopath,” the brilliant but eccentric Holmes dances the line between good and bad, fighting villains with a cold, calculated manner. True-hearted and kind, Watson follows to help and document.

In fact, while Doyle’s stories focus heavily on the intricate, fascinating plots, BBC chooses to further develop the characters and their relationships. In “The Hounds of Baskerville,” the reclusive Sherlock declares to Watson that he doesn’t have any friends, clarifying later with “I don’t have friends. I’ve just got one.” Though tense at times, filled with misunderstanding at others, BBC brings to light the friendship between Sherlock Holmes and John Watson, bringing a very human, relational touch to Doyle’s ingenious stories.

Indeed, this is the power of film adaptations. Filmmakers, actors, and writers can recast stories already proven to be great and imaginative, adding new dimensions in a partnership across time with the original author.

Check back next week as we step into the very different worlds of Jane Austen’s Pride and Prejudice and its two major film adaptations.

Open LORE's Sherlock Holmes Collection

--

Sherlock image (c) BBC